Izak Barnard THE SAFARI PIONEER

As a five year old barefoot boy, Izak Barnard loved to run to the post office, pushing the family wheelbarrow. The fact that the post office was 14 kilometers away didn't bother him much...

Today, more than 60 years on, he is still on the road to discover new things. Since childhood, the wheel fascinated Izak Barnard. He has traveled millions of kilometers: most of them in one of his beloved International 4×4 trucks.

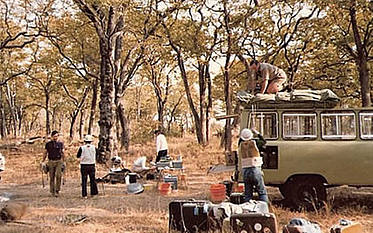

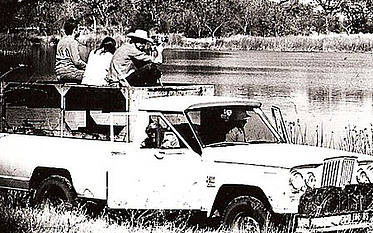

Izak, now 68, can rightfully be called the pioneer of 4×4 safaris in Southern Africa. As long ago as 1963, he started exploring the then undiscovered beauty of Botswana and established his own safari company. He named it Penduka Safaris. (“Penduka” is a morning greeting in Herero and means: “Did you get up well?”)

Penduka Safaris has grown quite considerably since those early days and today his son Willem, is at the helm. Yet, in many cases, it is still Izak’s reputation that sells safaris.

The middle child of the notorious Ivory hunter, Bvekenya (Cecil) Barnard on whom TV Bulpin’s book, “The Ivory Trail” was based. Izak loved to hear stories about distant, unknown places.

His father Bvekenya (“The one who swaggers as he walks”) started following the Great North Road in 1910. Until 1929, he had led adventurous, but hard life hunting.

Until his death in 1962, he and his family farmed on “Vlakplaas” in the then Western Transvaal.

Izak had also heard intriguing stories about a faraway place called Ngamiland from his mother’s family, the Badenhorsts, who owned the first shop at Lake Ngami in the 19th century.

“When the family came to visit, the children pretended to play under the table, but we were actually listening to the stories the grown ups told about the Dorsland Trekkers, the Kalahari and my father’s adventures as a hunter.”

zak recalls. “These stories had a major influence on my life.” As an 18 year old, Izak accompanied his 65 year old father to the north of the Kruger National Park, where Bvekenya showed Izak how to track. They visited old graves of friends as well as the remains of places that used to be full of life, when Bvekenya was still the great hunter.

When Izak wasn’t needed on the farm, he went in search of other work to occupy the quiet months. He even worked on a whaling ship.

“I did not like to see the whales being harpooned and skinned. I also do not like the sea,” he says. “When a ship sinks, you don’t stand a chance at all. But if your car breaks down in the Kalahari, you do have a chance.”

In 1953, at the age of 20, he bought his first engine-driven transport, a second hand 1947 ford. At this time, he was playing rugby for the local first team, and other interests were water skiing and tap dancing.

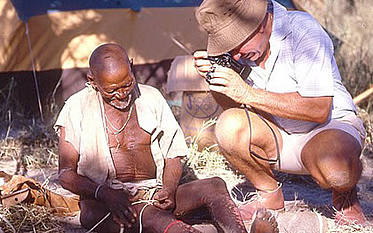

However, his first visit to Botswana (then still Bechuanaland) only happened 10 years later, and it changed his life. He and his friend, Quintus Knobel, who grew up in Botswana, borrowed a jeep station wagon to visit the Bushmen at Ngware. “I had heard many stories about the Bushmen – that they are half human, half animal. But when I met them, I realized that they were wonderful refined and gently people.”

Some of the Bushmen could speak Tswana – as could Quintus – and Izak realized the importance of learning another language. Today he speaks Setswana fluently.

During that visit to Botswana Izak realized that safaris could become a way of life and a career. “Bechuanaland was such a lovely country and I began thinking of showing it to other people.”

The following year he and three friends took his two wheel drive a Nissan Junior one ton bakkie to Ngamiland, the place Izak had heard of in his childhood. They often got stuck on the very sandy road to Ghanzi and Ngamiland, unable to go forward or backwards, and the engine overheated all the time.

Four wheel drive vehicles were practically unheard of in those years: “most of us were well prepared for two wheel driving, though. We never went anywhere without spades and we used to put branches under the wheels to help us get out.”

“When four wheel drive vehicles were introduced we thought it was just a question of getting in and driving off. We didn’t know there were skills involved. But we learnt very quickly.”

Traveling in desolate areas, Izak had to learn everything he could about the mechanical side of his vehicles. Later he would use this knowledge to “quickly” replace engines or fix gearboxes under trees in the Kalahari, or straighten a bent axle with chains attached to a tree trunk.

Several expeditions to destinations in Botswana followed and soon he started advertising for paying customers. Izak knew this was the way he wanted to spend his life. Fortunately, he was married to a wonderful wife, Anna Reichert, who took over the farming activities while he was in the bush and helped him prepare for each safari.

Izak has an extraordinary Knowledge of trees, grasses, plants, birds, mammals, reptiles, world politics, astrology, history, geology, and a myriad of other subjects.

Today he owns more than 3 000 books on various topics. His photographic memory helps him to remember almost every fact he reads. He has also been a National Geographic subscriber since 1963 and he has a collection of thousands of old magazines.

Izak also has other talents. About 15 years ago Penduka Safaris was contracted to take a film crew to Mier near the Kalahari Gemsbok Park. The advertising agency required the crew to film a 4×4 bakkie “flying” over the red sand dunes. A stunt driver from Australia tried without success and finally Izak, who sometimes has a short fuse, decided to show them how it’s done. He loaded a few bags of sand on the back of the bakkie for balance and flew over the dune. The advertisement was screened on local television many times, the windows of the vehicle blacked out, however, to hide the identity of the real stunt driver”

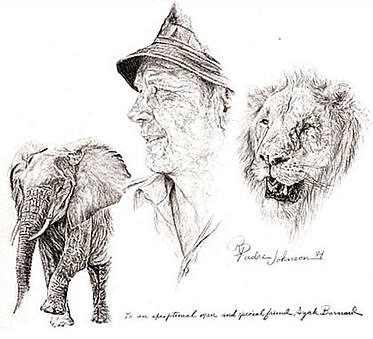

In 1984 the American painter Padre Ray Johnson accompanied two Americans on safari to record their experiences on canvas. One night, sitting around the campfire at Savuti two male lion started fighting nearby and got uncomfortably close to the group. To their amazement, Izak got up and, using an ordinary garden rake, pushed one of the lions away from the group.

A few days later in Chobe Game Reserve a heard of elephants mock charged the vehicle and the occupants got the fright of their lives, but Izak, who knows elephants and realized they were actually in a good mood, got out and chased them away by waiving his arms. This made such an impression on the group that Izak later received a lovely painting showing himself, an elephant and a male lion. The inscription reads: “To an exceptional man and special friend, Izak Barnard.”

Unlike his father, Izak is not a hunter. But he has “shot” hundreds of excellent photographs. He got his first camera in the late 1970’s when a group of Japanese clients presented him with a Canon AE1 and a 300mm lens. He became a keen photographer and took many award-winning shots, although he never entered any competitions.

Some of his Bushmen photographs are on permanent exhibition in the Smithsonian institute in America. Today he owns three Canon cameras, with lenses ranging from a 17mm to an 800mm.

Izak’s unusual knowledge of the Bushmen and his special relationship with them are also well known among researchers.

Izak, however, shuns fame and celebrity. He will rather tell you about the time when he and Simon Kooper found their way through the Kalahari with the help of only the sun, shade and the sand dunes.

That happened in the early 1960’s when Izak wanted to find the old ox wagon trail from Hukuntsi to the Gemsbok Park. People told him that it didn’t exist anymore, but Izak spoke to Simon Kooper, the leader of the Nama Hottentot people in Botswana. Simon told him: “I know the way. We used it when we walk to “Duits-Wes Afrika’.”

According to Izak, Simon taught him “to get back to Hukuntsi, the sun must shine on our foreheads, between our eyes. And when we reach that spot, the sun must shine in our left eye.”

Izak, however, shuns fame and celebrity. He will rather tell you about the time when he and Simon Kooper found their way through the Kalahari with the help of only the sun, shade and the sand dunes.

That happened in the early 1960’s when Izak wanted to find the old ox wagon trail from Hukuntsi to the Gemsbok Park. People told him that it didn’t exist anymore, but Izak spoke to Simon Kooper, the leader of the Nama Hottentot people in Botswana. Simon told him: “I know the way. We used it when we walk to “Duits-Wes Afrika’.”